To translate words with more than 2-3 characters requires knowledge of this ancient language. I figured out the key by which the first section could read the following words: hemp, wearing hemp food, food (sheet 20 at the numbering on the Internet) to clean (gut), knowledge, perhaps the desire, to drink, sweet beverage (nectar), maturation (maturity), to consider, to believe (sheet 107) to drink six flourishing increasing intense peas sweet drink, nectar, etc. Moreover, in the text there are 2 levels of encryption. Characters replace the letters of the alphabet one of the ancient language. The Voynich manuscript is not written with letters. With her help was able to translate a few dozen words that are completely relevant to the theme sections. Part of the key hints is placed on the sheet 14. The key to the cipher manuscript placed in the manuscript. There is a key to cipher the Voynich manuscript.

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into ClothesĬarl Jung’s Hand-Drawn, Rarely-Seen Manuscript The Red Book: A Whispered Introduction Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books Good luck!ġ,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online Another privately-run site contains a history and description of the manuscript and annotations on the illustrations and the script, along with several possible transcriptions of its symbols proposed by scholars. Or flip through the Internet Archive’s digital version above.

DECODED VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT CRACK

Should you care to take a crack at sleuthing out the Voynich mystery-or just to browse through it for curiosity’s sake-you can find the manuscript scanned at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which houses the vellum original. Surely in the last 300 years every possible import has been suggested, discarded, then picked up again. Maybe it’s a relic from an insular community of magicians who left no other trace of themselves. “Why on earth would anyone waste their time creating a hoax of this kind?,” he asks. This is a proposition Stephen Bax, another contender for a Voynich solution, finds hardly credible.

The degree of doubt should be enough to keep us in suspense, and therein lies the Voynich Manuscript’s enduring appeal-it is a black box, about which we might always ask, as Sarah Zhang does, “What could be so scandalous, so dangerous, or so important to be written in such an uncrackable cipher?” Wilfred Voynich himself asked the same question in 1912, believing the manuscript to be “a work of exceptional importance… the text must be unraveled and the history of the manuscript must be traced.” Though “not an especially glamorous physical object,” Zhang observes, it has nonetheless taken on the aura of a powerful occult charm.īut maybe it’s complete gibberish, a high-concept practical joke concocted by 15th century scribes to troll us in the future, knowing we’d fill in the space of not-knowing with the most fantastically strange speculations. It turns out, according to several Medieval manuscript experts who have studied the Voynich, that Gibbs’ proposed decoding may not actually solve the puzzle.

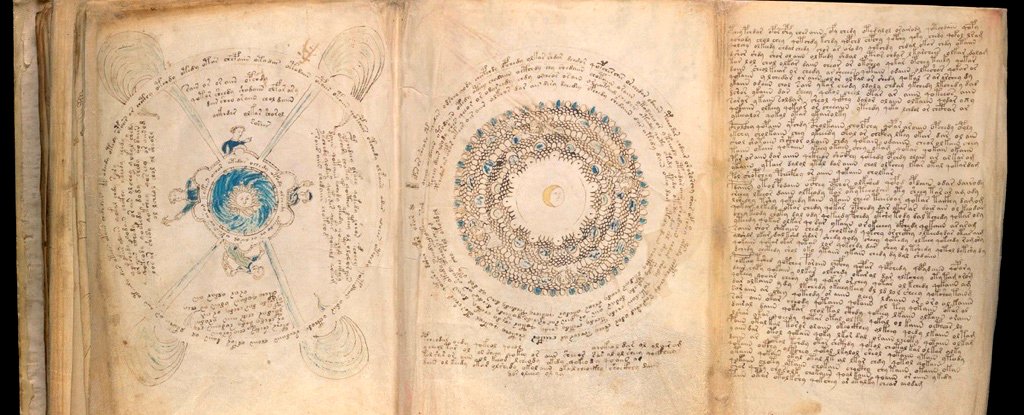

The manuscript’s “botanical drawings are no less strange: the plants appear to be chimerical, combining incompatible parts from different species, even different kingdoms.” These drawings led scholar Nicholas Gibbs, the latest to try and decipher the text, to compare it to the Trotula, a Medieval compilation that “specializes in the diseases and complaints of women,” as he wrote in a Times Literary Supplement article earlier this month. The manuscript’s origins and intent have baffled cryptologists since at least the 17th century, when, notes Vox, “ an alchemist described it as ‘a certain riddle of the Sphinx.’” We can presume, “judging by its illustrations,” writes Reed Johnson at The New Yorker, that Voynich is “a compendium of knowledge related to the natural world.” But its “illustrations range from the fanciful (legions of heavy-headed flowers that bear no relation to any earthly variety) to the bizarre (naked and possibly pregnant women, frolicking in what look like amusement-park waterslides from the fifteenth century).” Scholars can only speculate about these categories. “Over time, Voynich enthusiasts have given each section a conventional name” for its dominant imagery: “botanical, astronomical, cosmological, zodiac, biological, pharmaceutical, and recipes.” A comparatively long book at 234 pages, it roughly divides into seven sections, any of which might be found on the shelves of your average 1400s European reader-a fairly small and rarified group.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)